Unifying the built environment: a framework for operational value

Despite the plethora of clever tech, a core challenge remains of bridging the gap between project delivery and the world of operations, writes Pete Swanson, digital tech lead at Mott MacDonald.

The journey of ‘smart’, ‘intelligent’, ‘digital’, ‘technology-enabled’, or ‘autonomous’ buildings has been a long and winding path over the past few decades. We’re still at a point where any discussion can be derailed by arguments over which of these terms is most appropriate. And yet, as we progress, the world is becoming more complex, more connected, and more demanding.

The true problem, however, isn’t just the chaos of definitions but the persistent and costly gap between the world of project delivery and the world of building operations. This fundamental disconnect, between the teams that design and build buildings and those that run them every day, is the core challenge the industry must solve. One thing is for sure: few, if any, practitioners can confidently say, “I know the whole smart landscape”.

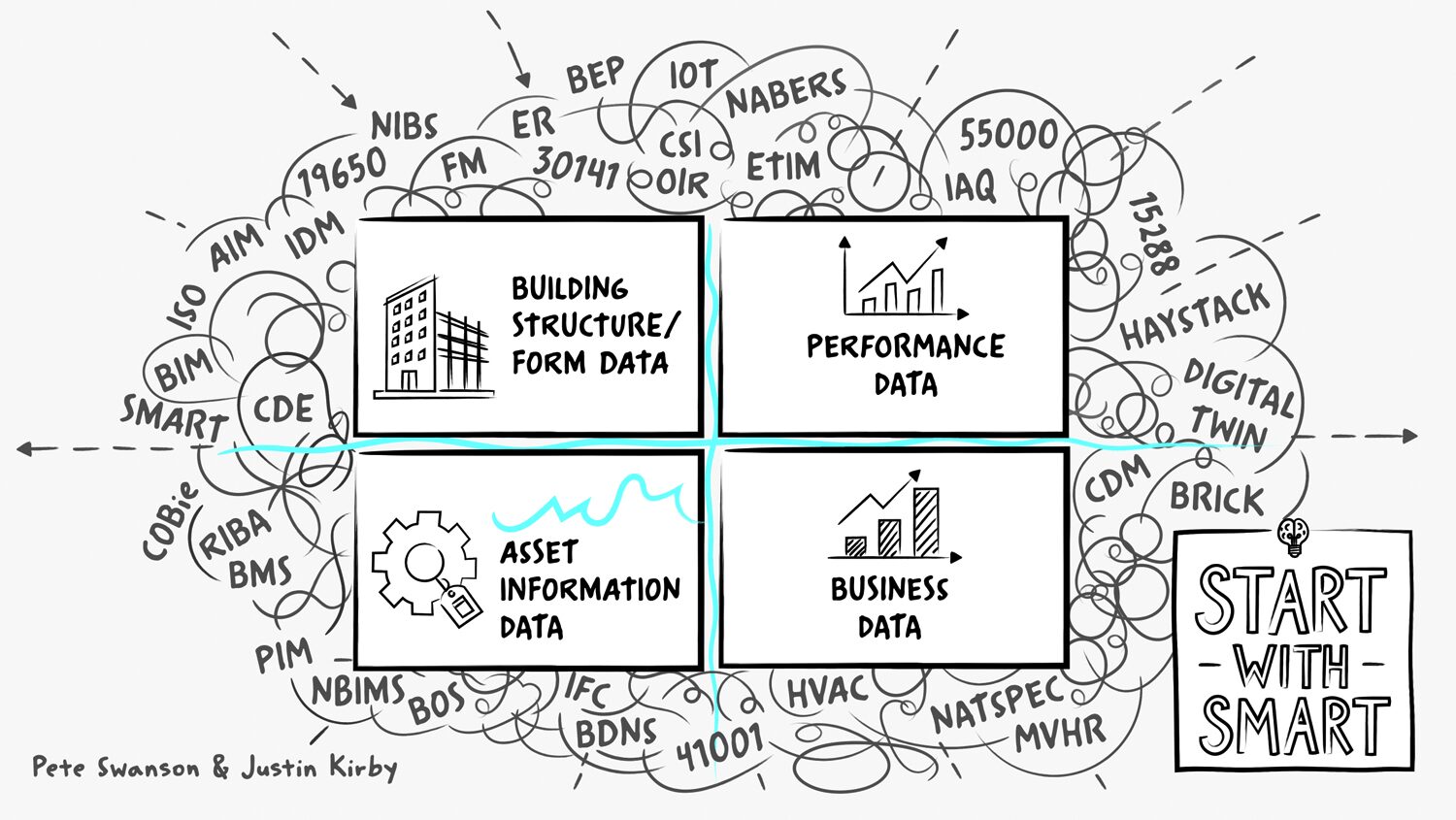

Under the broad banner of proptech, there are offerings that span at least four major areas of value and delivery with associated data categories:

- Building structure/form data: static information (architectural layouts, BIM, IFC);

- Asset information data: static-but-changing information (equipment lists, warranties, lifecycle data);

- Performance data: dynamic, real-time data (BMS, IoT sensor feeds);

- Business data: commercial and financial data (leasing, ESG, operational costs).

Each of these areas has been developing data practices for over a decade, and as a result, they have each established their own standards, guidelines and best practices for data structure, naming, sharing and application.

However, as solutions emerge that seek to use two, three, or all of these data categories, it’s becoming clear that most professionals focus on one of the four areas. They know their ‘home turf’ very well but may have little or no understanding of the others – or even awareness that they exist and have their own standards and guidelines.

This situation creates confused discussions and project dialogues in which each area tries to understand and interface with the others. But it is often unclear when, how, and with whom those project discussions should take place.

The most common issue today is forgotten scope, where elements such as the master systems integrator, the integration platform, data governance, or interface management may be entirely overlooked. Together with this, the view towards the operational lifecycle of the building is often obscured for the project team, meaning that what they design and document can be difficult to transition into effective operations.

Driving a new approach

There are other factors, too, such as the NABERS performance rating becoming an important consideration, particularly in the Australian market. And prior ‘grand vision’ smart platform deployments that frustratingly didn’t deliver hoped-for (yet typically undefined) outcomes. These, coupled with increasing demands for operational building performance outcomes, are driving an expectation for real results – and not a moment too soon.

This situation focuses minds on joining the dots between digital building design, enablement and management. That’s why we have presented these data categories not as a definitive list, but as a basis for discussion to help reach common agreement before delving into what each may contain, including standards and data schemas. For example, without occupancy data from building sensors being available in the business data category, the discussion may be a bit moot.

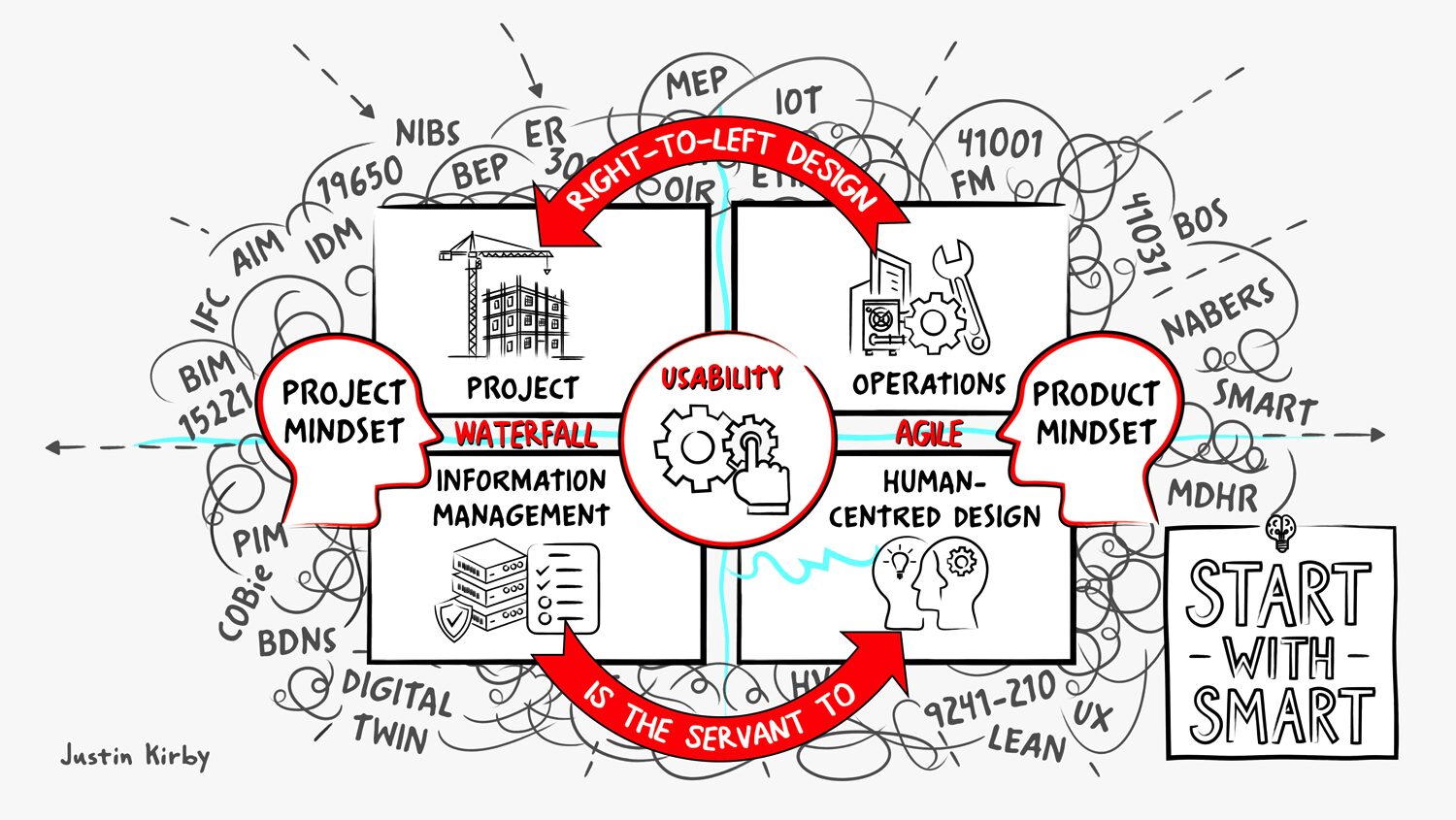

The idea here is to use a human-centred design lens to look at how to bridge the divide between project delivery and operations. This means thinking of the data categories from the perspectives of the key owner, operator, and occupier stakeholders. Instead of building a framework around a technology stack, we are building one that uses those technical data categories as tools to serve the pains, gains, and jobs-to-be-done of the key stakeholders.

This could be a starting place for a discussion about a digital soft-landing framework. This could then feed into a review of the Smart Building Overlay to the RIBA Plan of Works to provide a common view of available standards and tools. The data categories, for example, could be used as rows that don’t just cut across the columns of the eight stages, but also possible sub-rows. This would be especially useful during handover as responsibilities are extended through performance-related contracts.

The core principle is that a clear view of the required data types, structures, and responsibilities would be established early in the contract, so that there is clarity for all project stakeholders on what is required, and when, for each category.

Industry dialogue is essential

One key example is a minimum viable handover requirement (MVHR), which defines the essential, high-value data needed by the operations team. This shifts the conversation from a bottom-up, technology-centric push in the latter stages of project delivery to a top-down, human-centric pull, ensuring that the digital enablement of a building is purposeful and provides tangible value from day one.

This framework is not an endpoint: it’s a starting place for an essential industry dialogue. The ideas presented here emerged from a vibrant, multidisciplinary conversation in the Start With Smart group, where we believe that true progress comes from collaboration and a willingness to question the status quo. We invite you to share your feedback and to join the discussion as we collectively work to solve this core challenge.

Co-authored by Pete Swanson, Digital Tech Lead at Mott MacDonald (Australia), and Justin Kirby, industry commentator, connector and facilitator of Start With Smart.

Keep up to date with DC+: sign up for the midweek newsletter.