Model before you promise: why digital planning must start at the policy stage

The public sector should adopt a digital-first approach, modelling projects for deliverability before publicly announcing them and making promises that can’t be kept. Proicere Digital’s Dan Ashton explains the steps that should be taken.

When the government announced in September that plans for new train infrastructure in the north of England would be delayed, ministers were quick to stress that they wanted to avoid “another HS2”. The high-speed rail project – like so many public projects – has become a byword for spiralling costs, exaggerated promises, missed deadlines and political headaches.

But the lesson from HS2 is not just that the UK needs tighter budgets and more rigorous oversight: it is that projects are often politically committed before they are technically validated. Announcements come first, reality checks later. And by the time the technical detail is stress-tested, ministers have already promised a scheme that may never be deliverable as sold.

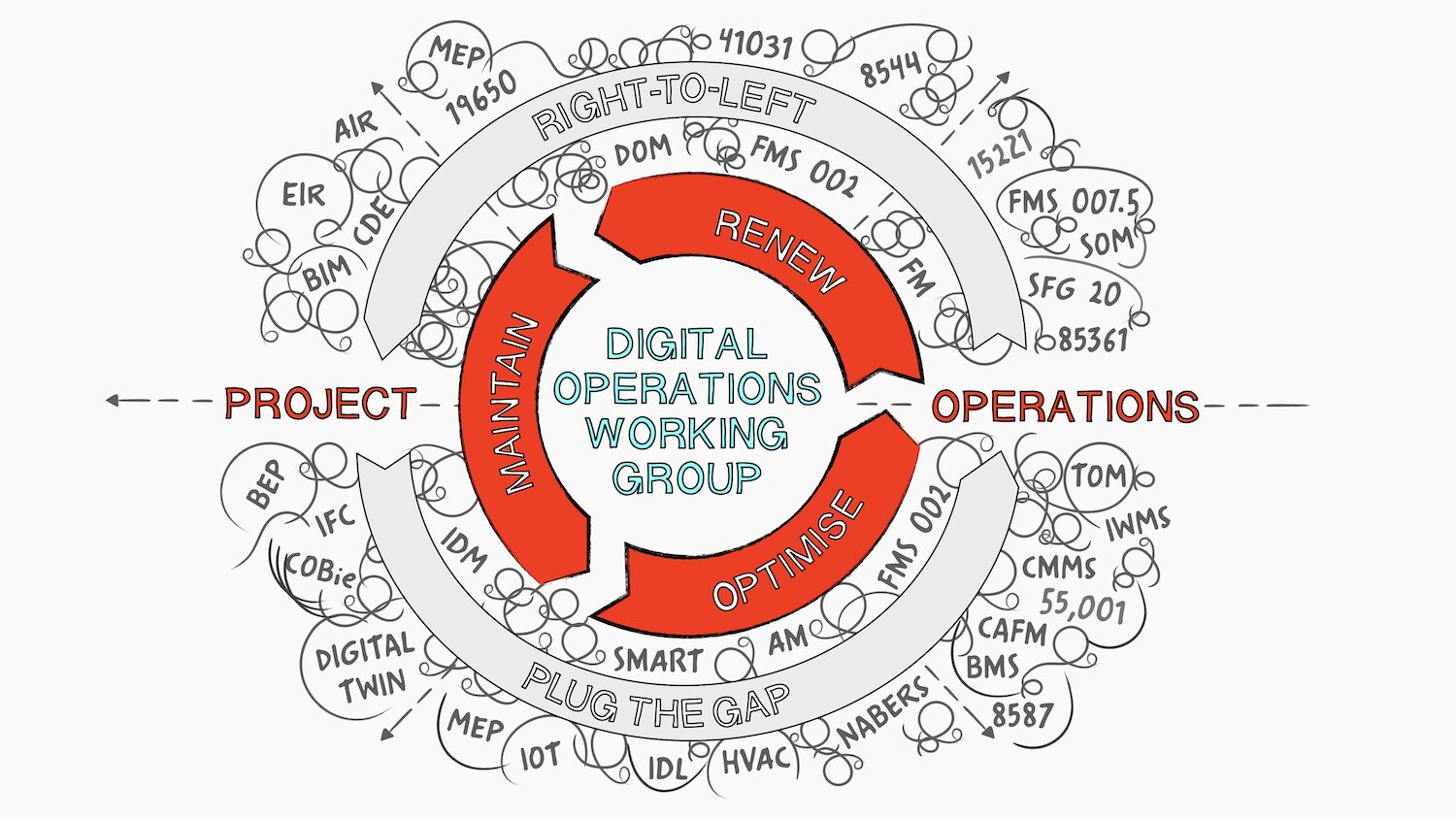

This is precisely where digital planning tools, such as 4D construction sequencing, BIM and, arguably more importantly, digital twins could make the difference. The technology exists to simulate, model and interrogate a project before ground is broken. The problem is that in the UK, these technologies tend to be introduced after political announcements, not before.

Digital ‘after the fact’

HS2 is a case in point. The project’s ‘Virtual Railway’ digital twin now in use allows engineers to simulate rail operations and construction logistics in detail. Yet by the time it was deployed, fundamental decisions on route, scope and budget had already been made. Digital modelling was applied to deliver the scheme more efficiently, rather than to validate the scheme before it was announced.

The National Audit Office (NAO) has alluded to this problem, calling for stronger governance of publicly funded ‘mega-projects’ in its March 2025 report. BIM, meanwhile, has been mandated for centrally procured projects since 2016, but mainly at the design and delivery stages. While BIM is mandated on centrally procured projects, consistent early-stage use (before design freeze) remains patchy across the UK public sector.

Countries such as Singapore and Denmark take a more proactive approach, embedding digital modelling early in public projects. In Singapore, BIM supports planning and approvals; in Denmark, public clients expect BIM deliverables from the concept stage. While not every project begins with a full model, both show how early adoption leads to stronger policy and design decisions. The UK is still behind in applying digital planning as a policy tool rather than a delivery aid.

The government’s pain points

It is too simplistic to expect government departments to invest in digital earlier, for the following reasons:

- political timing pressures – ministers are under pressure to announce bold projects quickly, often before detailed feasibility work is complete;

- skills and capability gaps – civil service teams may lack the in-house expertise to commission or interpret complex digital models;

- procurement inertia – current procurement rules make it cumbersome to bring in digital consultants at the ‘ideas’ stage without triggering lengthy tenders; and

- budget optics – spending millions on consultants before a project is even approved risks being painted as wasteful.

These challenges must be acknowledged if we aim to make digital planning part of government decision-making culture.

4D planning: upfront costs, but big savings downstream

The budget optics are particularly tricky. Ministers know that if they announce early spending on consultants, they risk excoriating headlines in the Daily Mail or a grilling on the Today Programme. Yet this is precisely where digital planning needs reframing.

Admittedly, digital planning requires greater upfront investment compared with traditional planning. Creating a 4D model of a project, running digital twin simulations, or commissioning integrated BIM models is not cheap. But the savings, created through risk avoidance, are orders of magnitude greater.

It is well documented that the later design changes are made, the more significantly these changes increase costs due to rework, wasted time and lost productivity. Studies show that design and construction rework can add between 5% and 15% to project costs – increases that are often avoidable through better upfront planning.

Every pound spent on digital planning at the start saves many more in avoiding redesign, compensation and cancellation later. It is far cheaper to discover a clash or an unrealistic timetable on a digital model than to re-engineer concrete already poured.

A 4D schedule allows stakeholders to explore how tasks interact in time and space, in a way that is not possible with static 3D models. This includes ensuring access, avoiding rework and safely coordinating multiple trades and vehicle movements in confined areas. Time-lapsed simulations often expose risks invisible in static models, enabling design teams to resolve them before construction begins.

For one nuclear industry infrastructure programme exceeding £1bn in value, for example, our 4D workflows helped identify more than £80m in potential rework. Extrapolate that for a project like Northern Powerhouse Rail, with a conservative estimate of £5bn, and it is reasonable to assume avoidance of errors that would have cost the taxpayer upwards of £400m.

“Creating a 4D model of a project, running digital twin simulations, or commissioning integrated BIM models is not cheap. But the savings, created through risk avoidance, are orders of magnitude greater.”

Practical solutions

Modern governance no longer relies solely on paper-based reviews. Digital assurance systems demonstrate how AI and automation can continuously test project data, giving decision-makers live confidence in cost, schedule and scope before approvals are made.

How, then, can the government embed digital earlier without creating new bureaucracy or political risk? Here are some practical solutions for overcoming resistance and winning over the sceptics.

Policy sandboxes: commission short, contained digital modelling exercises known as ‘sandboxes’ at the policy stage, to test assumptions confidentially before projects are announced.

For example, using existing data from Network Rail, Ordnance Survey and local authorities, a small team of digital consultants would build lightweight 4D and BIM models of several rail route or delivery options. These models would simulate real-world issues such as costs, timelines, development of land, logistics and carbon impact, giving policymakers a clear view of feasibility before promises are made. If exposed as weak by modelling, the concept can be quietly dropped. But if a strong concept is validated, the government can proceed with the confidence that the plan has been stress-tested against data instead of wishful thinking.

Capacity building: pair consultants with civil servants to train teams, so government departments become ‘intelligent clients’ of digital tools – levelling up knowledge!

A digital consultancy can help ‘level up’ knowledge through short, non-technical training sessions and live demonstrations that show policymakers how to ‘read’ and interrogate digital models, challenge assumptions, and use visual evidence to guide decision-making. The aim here is to equip civil servants and ministers with the ability to ask the right questions early, justify digital investment publicly, and make evidence-based infrastructure decisions.

Tie digital validation to public funds: while the UK already has a series of project assurance checkpoints thanks to the Infrastructure and Projects Authority’s Gateway Reviews and the Five Case Model, these processes still rely largely on paper-based evidence.

A natural evolution would be to embed digital validation into these gates, creating a ‘model before you promise’ step that uses live BIM, 4D and digital twin data to prove feasibility before public commitments are made.

Data and models can be questioned before policy announcement and later, before parliamentary approval, to confirm that assumptions about cost, time, land use and environmental impact are supported by evidence. Each model offers the opportunity to test assumptions, challenge optimism bias and, if necessary, make fundamental changes, such as a course adjustment.

Prove value through transparency: the hiring of consultants in the public sector tends to be associated with waste and hollowing out of in-house expertise. It is therefore vital for the government to keep a sceptical media and electorate onside by being transparent about how a digital approach delivers measurable returns.

To demonstrate value, therefore, departments should publish data showing the cost of early digital modelling compared with the cost of overspends and delays avoided. Regular reports may describe the uncertainties that were clarified, what options were ruled out, and the value of potential overspend that was prevented. Digital spend may thus be regarded as an insurance premium that protects both taxpayers’ money and the government’s reputation.

A chance to restore credibility

The UK’s infrastructure credibility is fragile. HS2 is only the latest in a string of projects that have eroded public trust in government promises. The decision to delay northern rail proposals underlines the fear of repeating mistakes.

Adopting a digital-first mindset at the policy stage is not a panacea. Political realities, procurement rules and capacity limits will always shape what is possible. But it is a powerful way to reduce the risk on public projects before ministers go out on a limb.

If governments do not model before they promise, they risk promising what they can never deliver. And if they cannot deliver, no amount of reannouncements, rephasing or rebranding will restore credibility.

The good news is that today’s 4D digital planning technologies have proved their value in construction and the manufacturing industry. Moreover, by harnessing AI, these technologies are likely to become only more powerful – analysing more datasets, from logistics to environmental constraints, identifying patterns that humans miss, and generating optimised scenarios faster.

All that is required is the will to use digital planning as a tool for policy formation, not just delivery. It is, after all, much cheaper to find problems on a computer screen than in concrete.

Keep up to date with DC+: sign up for the midweek newsletter.