Construction’s great stagnation

So much time and money has been spent on digital transformation, but the industry has not truly transformed. Indeed, Neil Irving contends that construction has stagnated. Here is an abridged version of his recent Substack post that reflects on construction’s great stagnation.

Over Christmas, I read Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber. In it, the “great stagnation” is framed as a slowdown in real progress: fewer step-changes, more marginal gains, more optimisation theatre.

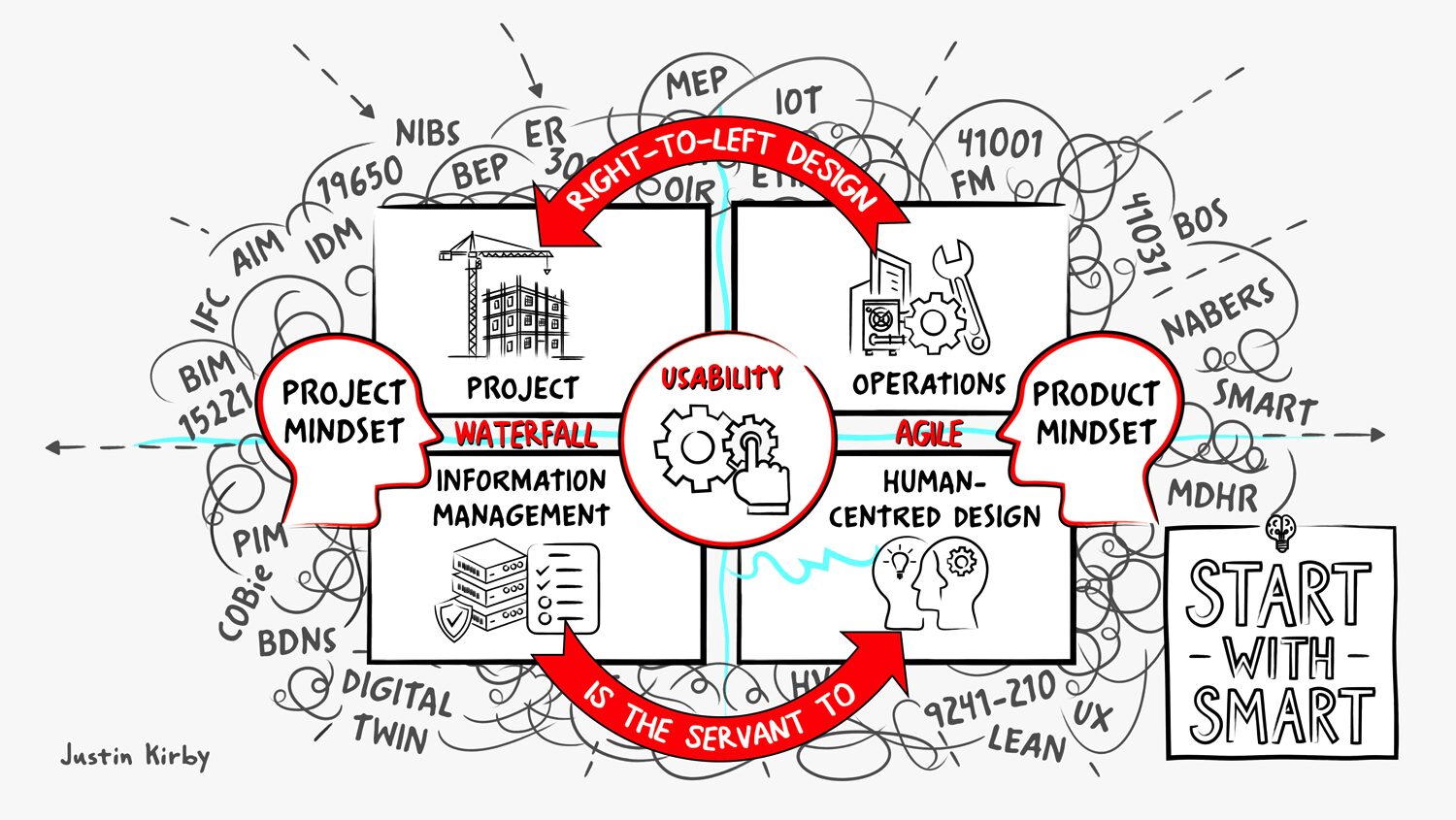

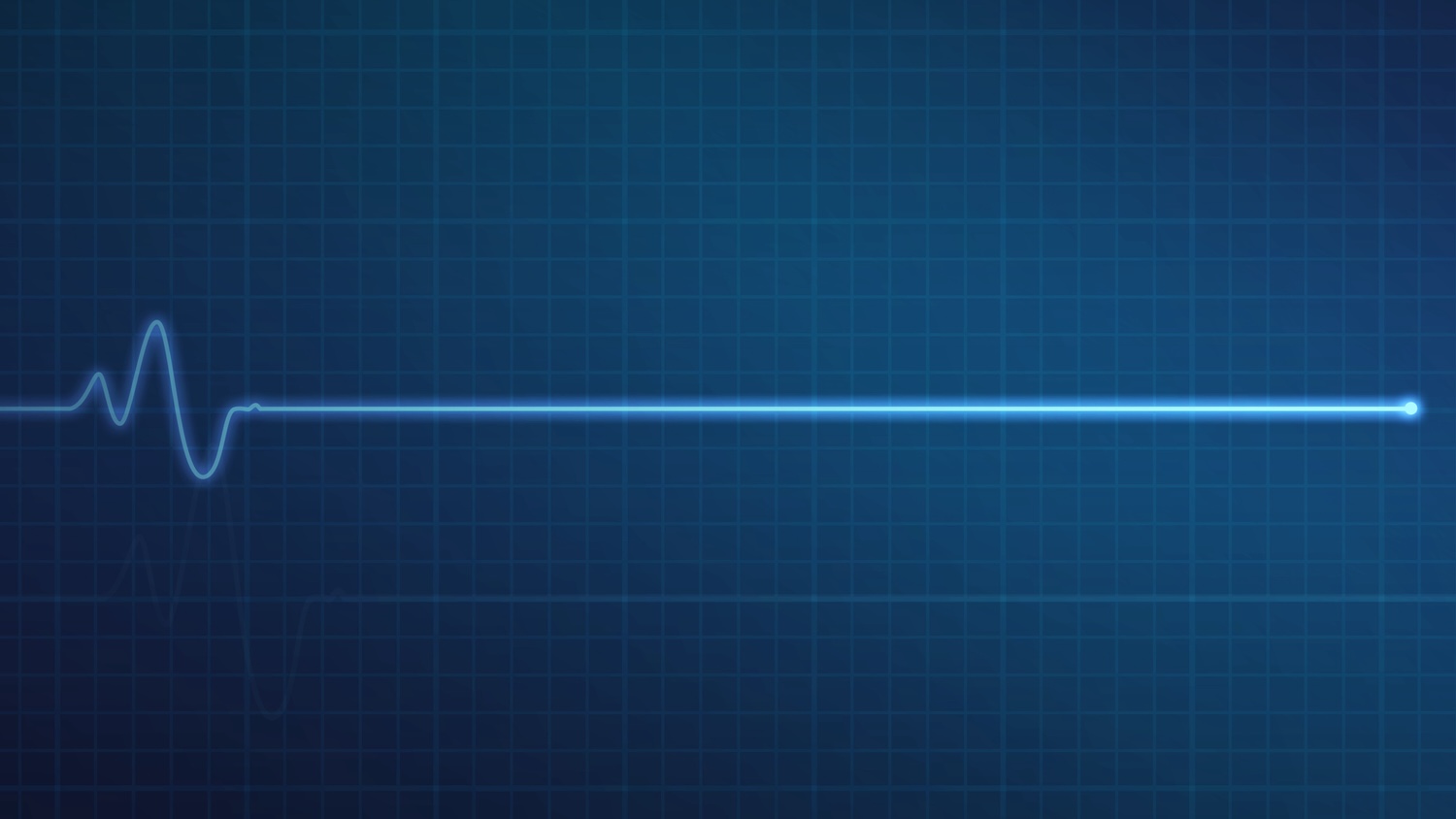

Seen through a construction lens, the diagnosis is brutal. Construction hasn’t stagnated because we failed to digitise: it has stagnated because we digitised the wrong things. We swapped paper for pdfs, drawings for models, folders for CDEs – but we are leaving the production system relatively untouched.

What actually happened:

- productivity flatlined for 30-plus years;

- projects got more complex, not faster;

- compliance expanded faster than capability;

- risk was pushed downstream, not removed; and

- ‘innovation’ became software procurement, not system change.

BIM didn’t change how we build: it changed how we describe what we intend to build. That’s not real progress: that’s better documentation of inefficiency.

While being able to coordinate design and review buildability more easily has brought some improvement to planning the build, there are very few examples of progress beyond the preparation and information gathering phase.

The industry optimised coordination costs while ignoring throughput, variance and decision latency – the real killers. That’s where construction’s stagnation lies.

Explainer: variance, throughput and decision latency

Variance = the gap between what was planned and what actually happens – in time, cost, quality or sequence.

Throughput = the rate at which the system converts inputs into completed, accepted work.

Decision latency = the elapsed time between a decision being needed and that decision being made and acted upon.

If we can accept this, then what would actually count as real innovation?

Three opportunities for genuine progress

Industrialisation immediately removes three constraints:

- variability – the delta between plan vs reality is narrowed;

- labour dependency – the workforce can be mechanised more readily; and

- learning rate – lean and continuous improvement can be more easily implemented.

A factory learns. A project forgets. When work moves from site to factory, the output becomes repeatable, quality variance disappears, and productivity compounds instead of resetting to zero on every job.

This is why manufacturing got rich and construction didn’t.

But we have MMC, right, so what went wrong? We tried to finance MMC before we standardised it: every ‘platform’ was bespoke in disguise – and clients demanded uniqueness when factories need sameness.

To make genuine progress, industrialised construction needs to look towards: brutal standardisation of interfaces; fewer typologies, not more; and platforms treated as products, not projects.

If it doesn’t feel uncomfortable to architects and clients, we’re not industrialising enough.

Decision automation at the production edge

Construction isn’t slow because people are lazy, it’s slow because decisions queue up. Every day, on every project, people are waiting for information, approval, clarification or assurance.

Most digital tools just move the queue onto a screen. To generate progress here, we must address the queue by:

- pre-authorising decisions;

- embedding deterministic rules;

- automating compliance checking; and

- requiring human intervention only by exception.

Some examples of this are:

- automated permit validation;

- deterministic design rule checking before issue;

- real-time quality acceptance at point of install; and

- commercial rules enforced upstream, not after the fact.

If an excavator is standing still waiting on a decision or information, the system is broken.

Information as an asset not a deliverable

Construction treats information as something you hand over, not something you compound. Every project relearns the same lessons, rebuilds the same spreadsheets, rewrites the same risk registers and loses most learning at close-out. That is commercial suicide.

The real innovation is treating information like capital:

- structured once;

- reused many times;

- queried, not searched; and

- fed back into future bids, designs and methods.

This is where things like knowledge management (perhaps through knowledge graphs), capturing and recoding production data, and measuring cost, time, risk and quality signals become a competitive advantage, not a compliance burden.

Businesses that do this will price risk better, build faster and quietly destroy competitors who still start afresh on every job.

But wait… where are the robots?

Robotics matters, but not in the way most people sell it. Right now, robotics in construction sits in the same bucket that BIM did in 2012: overpromised, underintegrated and mostly bolted onto a broken production system.

Robotics is not the next excavator moment. It’s a force multiplier after you fix three preconditions: standardised work, deterministic sequences and digitally controlled decisions. Without those, robots just expose chaos faster.

The uncomfortable conclusion

Construction’s stagnation isn’t technological. It’s organisational and incentive-driven. Fragmentation, path dependence and misaligned incentives are the three causes of construction’s stagnation.

Real innovation reduces variance, improves decision time and increases throughout. Anything else is productivity simulation.

A simple question to ask as a litmus test is: “Does this innovation let us build the next project faster, cheaper or with fewer people – without heroics?”

If not, it’s not progress: it’s noise.

Read the full version of this on Neil Irving’s Substack. The opinions expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of his employer

Keep up to date with DC+: sign up for the midweek newsletter.