AI needs to be trustworthy – and good ethics can help

Charles Sheridan outlines why he believes trust must underpin AI development and deployments.

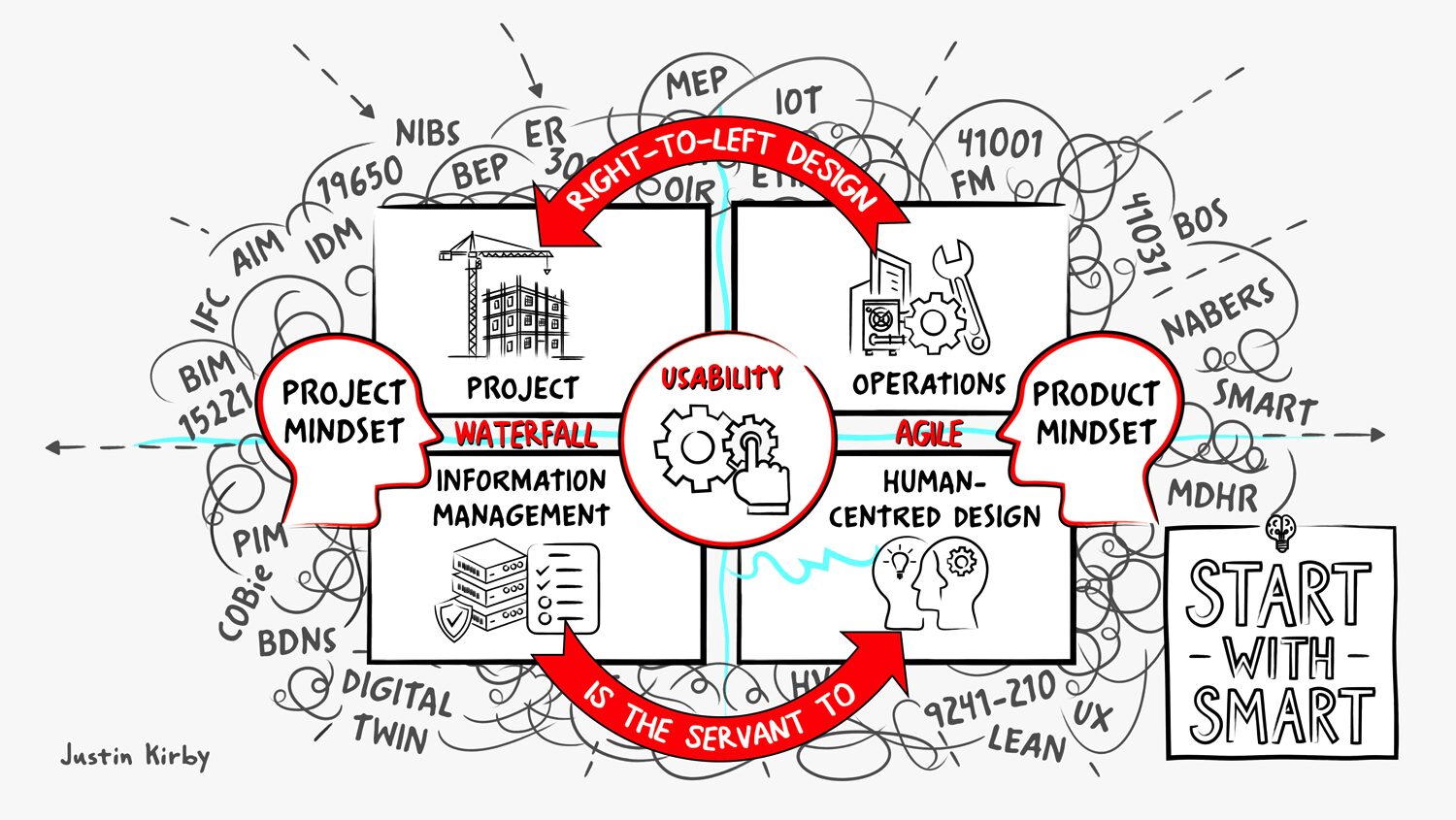

Trust is becoming the defining challenge of AI in the built world. Not just trust between client and contractor, but between user and tool. When software starts suggesting layouts, identifying structural risks or selecting materials, professionals need to know it’s working with them, not around them.

As we move towards more agentic AI systems, that kind of confidence becomes foundational. Without it, adoption stalls. With it, AI becomes a force, even a differentiator. It’s why ethics matters in AI. Not just in abstract terms, but in how AI behaves, how it’s governed, and how responsibility is shared. As European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen put it earlier this year, at the AI Action Summit in Paris: “AI needs the confidence of the people, and has to be safe.”

Don’t wait for Brussels

The EU AI Act is one attempt to formalise that. It introduces a risk-based approach to regulating AI systems, with stricter rules for tools used in safety-critical environments, including construction. Draft guidance on incident reporting and governance is starting to surface. But in practice, much of the heavy lifting will fall to the organisations building and deploying these tools. Responsible AI will rely far more on self-governance than statute.

Companies working in architecture, engineering and construction, already understand this because these are all sectors where trust is embedded in the business model, between clients and contractors, engineers and planners, regulators and developers. Buildings stand for decades, often centuries, so the stakes are always high, the timelines long, and of course, reputations matter.

But trust in AI is not only about safety and compliance, it’s also about ownership. In design-led industries like architecture and engineering, intellectual property is more than just legal language, for example. And when AI tools are used to generate layout options, simulate structural behaviour or optimise materials, there are always questions, such as: who owns the output? What rights do creators retain? How is originality preserved in a world of prompts and probabilities?

How creativity survives

Take a generative design tool that proposes a new facade or load-bearing structure. Where does authorship sit? Who signs off? If two teams feed in similar prompts and get near-identical results, how do they know their work is truly theirs? These aren’t legal niggles: they go to the heart of how creativity, authorship and accountability survive in an AI-assisted workflow.

Creative professionals want assurance that their ideas won’t be absorbed into a black box, repackaged and redeployed elsewhere. Ethical AI must protect that line between assistance and appropriation. It’s about reinforcing the role of the human in the loop, not as a supervisor of machines, but as the creative authority they support.

Ethical AI also means being honest about what’s changing. Automation, at its best, is about freeing people from repetitive tasks so they can focus on what matters. But in a profession built on judgment, intuition and experience, there’s a thin line between augmentation and quiet deskilling. If AI handles the first draft, the first check, the first recommendation – what’s left for the human?

Responsible AI should amplify expertise, not dilute it. This becomes even more important as we enter the next AI phase, with agentic systems that support tasks, but more importantly, pursue goals. Why is this important? Because agentic AI changes the dynamic entirely. These systems initiate processes. They are not just reactive. They break down goals, choose methods, and carry out tasks independently.

Questions about trust

In theory, that means faster progress and fewer bottlenecks. In practice, it raises deeper questions about control, oversight and trust. What happens when an AI makes a decision that the human didn’t ask for? Or worse, didn’t notice?

In the built environment, where mistakes carry structural consequences, that kind of autonomy could lead to significant risk, yet confidence in AI can’t be skin deep. It has to be rooted in transparency, tested over time, and aligned with how professionals actually work. If people don’t trust the agent, or understand it, they’ll bypass it. And rightly so.

Clear communication is part of this too. Users need to know when and where AI is involved in the workflow, what it’s optimising for, and how it reached a particular outcome. Black box logic may be acceptable in consumer apps, but in construction and design, decisions need to be explainable, especially when lives, costs or structural integrity are on the line.

The good news is, we’re not starting from scratch. Frameworks already exist to guide ethical AI in practice, from transparency and explainability to privacy, robustness, accountability and sustainability. These principles are fast becoming the conditions for trust, both within teams and across the industry.

And trust is the advantage. The firms that treat it as a foundation will be better placed to deploy AI with confidence, win over clients, and future-proof their reputation. Because whether or not regulation is in force, responsible AI is already a business decision. After all, AI ethics is trust, and trust is good business.

Charles Sheridan is chief AI and data officer at Nemetschek Group

Keep up to date with DC+: sign up for the midweek newsletter.